Our “Missed Madison” coverage begins with Frederick Wiseman’s 180-minute deep dive into London’s famed museum

National Gallery availability: Netflix | GoWatchIt

Renowned documentarian Frederick Wiseman may have just earned superlative accolades for In Jackson Heights from Reverse Shot (as part of Museum of the Moving Image), but his assiduous curiosity previously led him across the Atlantic to study National Gallery in Trafalgar Square, London. This comprehensive 180-minute documentary commences in a tour guide’s evocative lecture on the viewing context of Jacopo di Cione’s cherubic tri-panel altarpiece “San Pier Maggiore” in the Middle Ages’ profound piety, as she asserts that di Cione’s painting once acted as a sacramental channel from Earth to Heaven. While camera POV often imitates this concept of transcendence, Wiseman’s meticulously formal detail is without dramatic camera movements or voiceover narration. Instead, the intensity of the original artist’s expression paired with ever-changing interpretations and cutting-edge preservation lend this chronicle of the majestic Gallery its all-embracing nature, its universal appeal to the intellect as much as emotional memory.

Technical discussion of art may seem more familiar to modern culture in the way audiophiles debate the value of listening to jazz, soul, and psychedelic rock records on their native release format, acquiring uncompressed .WAV or lossless .FLAC files instead of MP3, or the value of remastering. Yes, National Gallery may insist on the scholastic approach, but it’s not out to expose or alienate its audience. Rather, it invites them into the ongoing conversation of the relevance of age-old artwork, much like the value of “classic” music, to modern life and future generations. Superficially, the film may be categorized as a semester’s worth of art history condensed into a three-hour feature with byline clichés about “art coming alive.” And that’s not a mischaracterization, but the rigorously inclusive filmmaking regards more than can be contained in the purposes of a non-essayistic review that doesn’t sprawl into the “TL;DR” category. Wiseman intersperses the Gallery’s numerous conservation efforts that involve solvents removing discolored varnishes with the museum’s board of directors/staff debating function of the institution and distribution of diminished public funds.

Although the names of the tour guides are rarely revealed, they are interestingly identified in the same way one would look upon the subjects in the Gallery paintings from thirteenth through nineteenth centuries. In this mirroring, reciprocal effect, Wiseman asks his audience to leave behind preconceived notions of the individual and simply absorb the content and interest in their voice, much like the refined minutiae in the works of the European masters featured in this decade’s famed exhibitions: Leonardo Da Vinci, Rembrandt, Hans Holbein, Titian, Nicolas Poussin, and J.M.W. Turner (the enigmatic subject of last year’s Oscar-winner by Mike Leigh), among others. The specificity of analyses from the men and women, including an x-ray that illuminates a painting underneath Rembrandt’s “Portrait of Frederick Rihel on Horseback” to a more simplistic but nevertheless engrossing talk of Titian’s homage to poet Ovid in “Diana and Callisto,” all possess invaluable insight into the transferable process of inspiration and creation.

Perhaps the most fascinating monologue comes not from one of the most prominent or presumably tenured guides but a younger man orating to a small group of teenagers on his personal motivation for seeking the arts. His talk turns to subjectivity and the difference between a still painting and other mediums (primarily, in the utilization of a span of time). Amidst the many adult eyes and ears, his invitation may be most critical at this point in their lives, dissolving the barriers of academia that separate the discipline of schooling and passionate hobby. It really feels as if the director is both mimicking the impression of viewing a painting, the telling of a story in a single image, and adjoining it with an adherence to a specific filmic verisimilitude that unravels over time and within the context of the exhibition, where new associations are revealed when they inhibit a single, singular space.

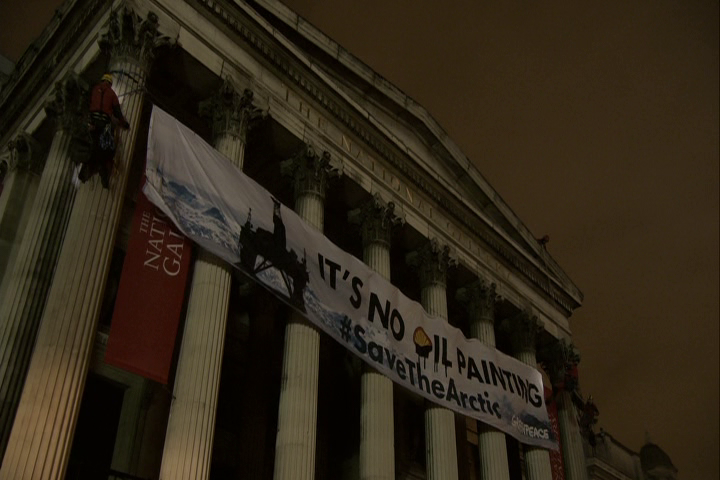

A little over halfway through, outside the walls of the museum, Greenpeace activists plan a public unveiling across its columns, employing the architecture as a forum for their own brand of activist art that addresses corporate polluters. “It’s No Oil Painting #SaveTheArctic,” their hundred-foot banner reads. The scene occupies little more than a half-percent of National Gallery‘s duration but provides a translucent window into the landscape and climate of modern London beyond the well-manicured, precisely furnished interiors adorned with the art of centuries past. The juxtaposition is stark but integral to the entanglement of life and art and the method in which to convey vital contemporary issues. If the artisans of the Middle Ages were attuned to spiritual enlightenment and obsessed with the divine in the congregation, then Millennials are drawn to the preservation of the Earth that’s irrevocably entangled with their own perseverance and artistic aptitude. Ponderous overviews like this sustain the documentary through the progressively truncated length of discussions and behind-the-scenes craftsmanship and executive council. It’s as if Wiseman comes to acknowledge his own mortality, letting the thought ironically affect his initially unobtrusive editing.

Of course, the dichotomous argument about the sacred and profane is less black-and-white and more reminiscent of critic Peter Bradshaw calling the Gallery a “secular cathedral of hushed grandeur.” His words tap into personal belief about art as therapy, which has existed since the time of cave drawings, expressed philosophically in the book by Alain de Botton, and persisting in present day, as we seek refuge in the cathartic, purging act. This directly relates to the initial tour guide’s quote about the painting as a portal from Earth to the Heavens, whether defined in the traditional sense of place or a more abstract, personal, indescribable definition that comes from knowing oneself more completely. In these terms, Jem Cohen’s narrative-essay film hybrid, Museum Hours (2012), is an intimate companion film, separated several degrees through form and presentation, but united by thread of art across time, country, language, and cultural barriers.

–

Be sure to check out other Missed Madison Film Festival reviews throughout the day:

Chris Lay on Bone Tomahawk; James Kreul on Hard to Be a God; and Jake Smith on Office at Madison Film Forum.

Ani Biswas on The Mend at WUD Film Presents.

Four Star Video Podcast‘s discussion of Cop Car.