Humanity’s choice between salvation and self-destruction is at the heart of every great Superman story

Yesterday afternoon, comics writer Mark Waid tweeted that he was spending his Father’s Day with his kids and watching The Iron Giant, in his mind “probably the best Superman film of all.” With Man of Steel crushing everything right now — from box office grosses to RottenTomatoes’s bandwidth to the expectations of at least one DC Comics fan — I took Mr. Waid’s suggestion to heart and rewatched Iron Giant , if only to see just how much the comparison actually works.

By now, most of us are familiar with the story. In grand American fashion, an alien crashes to Earth, embodying the journey of countless immigrants to the shores of Ellis Island or across Southern borders. With some considerable difficulty and a great deal of help, the he learns to blend in with surroundings, even as he’s not entirely suited for this planet. Of course, when that alien’s also a superpowered juggernaut with awesome strength and the ability to fly and even melt stuff with his eyes, it’s difficult to blend in anywhere, and sooner or later he is discovered. Countless Superman stories have strayed from this central arc, but including Snyder’s bombastic incarnation, it’s more or less the framework for the origin of Superman (err, Kal-el). It’s also the origin of The Iron Giant.

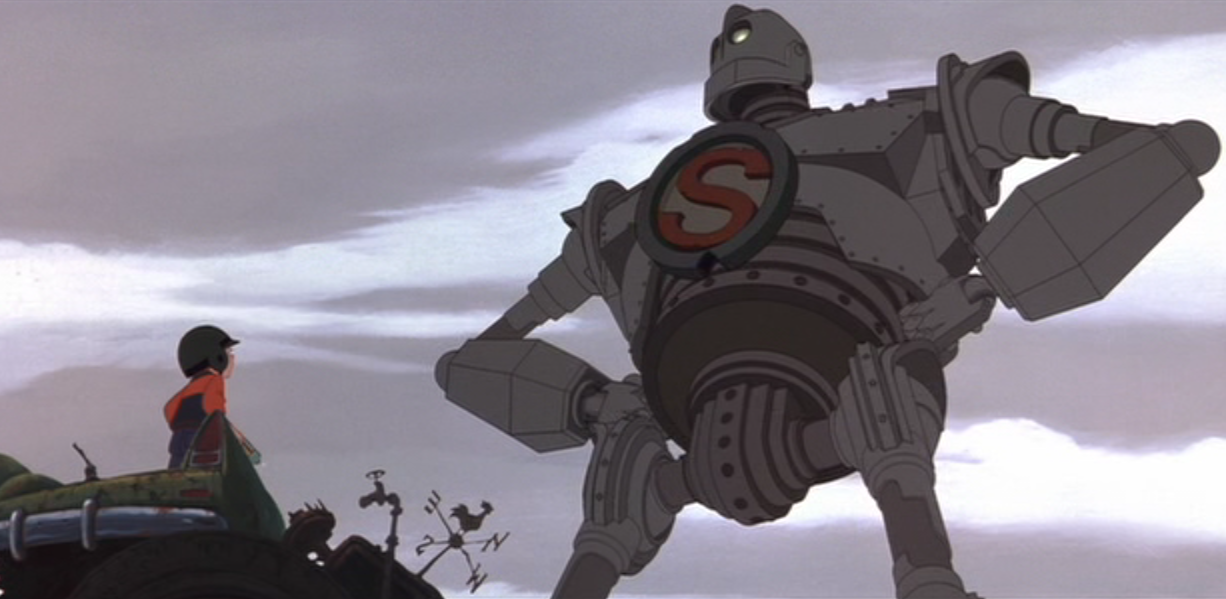

Loosely based on Ted Hughes’ 1968 novel The Iron Man (no, not that one), Brad Bird’s feature debut wears its influences on its sleeve, from serialized storytelling to science fiction of the 50’s and Amblin films of the 80’s. In drawing from the Boy in Blue himself, The Iron Giant wears his influence on its chest — literally in some cases — but Bird also takes a subtler approach in his tribute. He injects the film’s color palette with the warmth of a classic issue of Action Comics, muting the reds and souring the yellows thanks to the crisp New England fall setting. If that weren’t enough, blue is all over this picture and makes for some suggestive cues when paired with a cape or flying leap. Nearly a decade and a half later, The Iron Giant remains a gorgeous film, with hundreds of shots worthy of a picture frame and a spot on the wall — just like a comic strip.

Beyond its more subliminal reaches, The Iron Giant’s heart is in the relationships its titular character forms, namely the friendship he shares with a boy named Hogarth (Eli Marienthal). Like in most great Superman stories, there’s a give-and-take between our hero and the people he meets. Through the “Giant,” Hogarth learns to mature and take responsibility for his actions. His moral compass expands just as his understanding of the world around blossoms, and in the best way, Hogarth makes for a distillation of the citizens of Metropolis, those whom Superman affects and protects and inspires. And just as Kal-el imports his observed imperfections and idiosyncricies of humankind on his alter ego Clark Kent, the “Giant” learns to laugh and yell and make funny faces right alongside us.

The “Giant” doesn’t need to learn to kill, however; he’s been created with that capacity already, and it’s only a dent to his metallic head that’s stopped him from wreaking havoc on this small Maine town from the get-go. As a dormant machine of mass destruction, the “Giant” is a perfect realization of Cold War tensions, a “steam punk” remodeling of the Man of Steel. Out of atomic bomb emergency drills and columnists’ Sputnik satellite gossip, The Iron Giant posits a parallel world where the superpower is questioned. It’s a world where boundaries are not just drawn by geography or government, but through paranoia and ideology, and where the difference between a terrifying agent of destruction and a beacon of salvation ultimately rests with the collective decisions of humankind.

That choice is at the heart of every great Superman story, and it’s the centerpiece in The Iron Giant as well. The early Superman films of Richard Donner — and to a greater extent, Bryan Singer’s Superman Returns — found a spirituality in the character, a kind of transcendental connection between the Last Son of Krypton and the people of Earth, between an alien and his adopted planet. The “Giant” must choose to be good before he can be a hero. As credits rolled, I was reminded of the iconic words of Marlon Brando’s Jor-el: “They can be a great people, Kal-el, they wish to be. They only lack the light to show the way.” That inspiration, that capacity for good is what makes for a great Superman story. It’s also what makes for a great giant robot movie, even when said giant robot is voiced by Vin Diesel.