Bergman enthusiast Grant Phipps adds another entry on the tragicomedy that screens Sun at the Chazen

Inspired by G. K. Chesterton’s play Magic, Ingmar Bergman’s The Magician (or The Face as literally translated from the Swedish Ansiktet) is the tale of a mute magician named Albert Vogler (the immortal Max von Sydow) traveling through the Swedish countryside as part of his brand of charlatanism known as “Vogler’s Magnetic Health Theater.” Of the other twenty-plus Bergman films I’ve seen, looking at The Magician is, naturally, not as awe-inspiring as the psychological bravura of my introduction to end all introductions, Persona (#1). Gunnar Fischer’s cinematography is still visually possessive in its alchemy of elements from preceding successes, Smiles of the Summer Night (#15) and Sawdust and Tinsel (#10), while Bergman’s theatrical narrative predicts the heavy clash of Christianity and Paganism in The Virgin Spring (#16). Throughout the margins of my handwritten notes, “faith v. reason” prevails.

In the milieu of the mid-19th century when society was more susceptible to the allures of the supernatural, Vogler’s own grandmother (Naima Wifstrand) concocts medicinal potions for the public to sample (an image that recalls one in the second chapter of Benjamin Christensen’s silent cult film, Häxan). The travelling tonic theater has garnered such a reputation that it’s summoned to the home of Consul Abraham Egerman (Erland Josephson) on a bet between the man and medical adviser Vergérus (Gunnar Björnstrand, more Bergman regulars). Egerman is curious in matters of the spiritual and rumors that have circulated around Vogler’s character; the inherently dubious man of science, Vergérus, has staged a public humiliation for the false physician before a crowd of esteemed colleagues, a more-than-familiar theme in the Bergman filmography.

The writer-director reportedly conceived the script with a sizable cast in order to maintain their contracts, but it was a cumbersome rather than comfortable decision that breaks from Bergman’s perfect 90-minute run-time. Simply, there are too many bodies. Frank Gado, biographer of the critically exhaustive The Passion of Ingmar Bergman, discusses its uneven marriage of horror and comedy that mainly pertains to writing for such a troupe. Scenes involving Tubal (Åke Fridell), Vogler’s assistant/impresario, are handled lightly; Fridell essentially plays the same role as he did in Smiles of the Summer Night. Here, his jovial extroversion that woos the Egerman’s house cook, Sofia (Sif Ruud), is tonally inappropriate in the film’s sinister inclinations. The same goes for the entanglement of Sara (Persona‘s Bibi Andersson), a young maid, and Simson (Lars Ekborg), one of the coachmen. In general, the tonic part of the plot is handled adequately but almost ironically proves to be a distraction from focus on the validity of Vogler’s act, identity, and other typically Bergman-esque matters of the psyche.

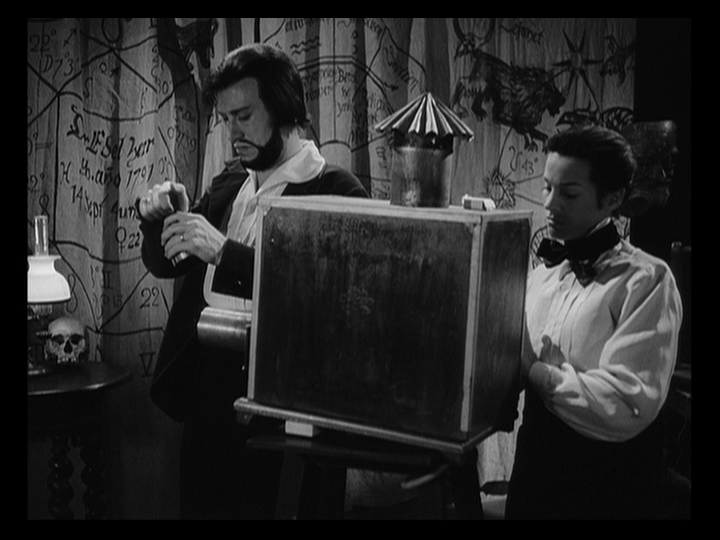

As the film progresses, my eye’s magnetically drawn to the magic lantern, a relic from Bergman’s childhood (that reappears so prominently in Fanny and Alexander, (Bergman film #9). Its presence symbolizes the director himself through the dichotomous view of Vogler’s magic show. On one hand, Vogler is a surrogate Bergman seeking revenge against his harshest critics (represented in Vergérus); and, on the other, it’s all self-deprecating tactic. Gado ends his analysis of The Magician by mentioning Bergman’s feeling of incompetency as an artist: cinematic conjuring is not a miracle, just another trick. And, while I personally appreciate this idealistic aspiration, it’s not instantly evident. Ultimately, The Magician feels like neither wonder nor chicanery; it’s just the product of writer’s block in the recycling from the director’s prior entries. There are still enough distinguishing features in the completionist’s quest to see every Bergman film, particularly the foray into mystical horror that would later evolve into more pronounced Gothic horror in Hour of the Wolf (#17). Dare to not be hypnotized by the interplay of light and shadow in Vergérus’ attic autopsy, which brilliantly (and literally) articulates Vogler’s sleights of hand.

The Christ parallels to Albert (that Bergman would continue to utilize a decade later in A Passion [of Anna], #19) begin to take shape during a drunken conversation between stableman Antonsson (Oscar Ljung) and servant Rustan (Axel Düberg) towards the midpoint. Both hold the idea that Vogler’s mysterious face or disguise is one that sets them on edge. Perhaps most vividly, Egerman’s wife Ottilia (Gertrud Fridh) is compulsively drawn to Albert (like I to the magic lantern), believing he is a fateful visitor to explain her child’s death. In essence, she has instilled the magician with the highest power of all – sheer belief – to ease her sorrow. “You must forgive them…. They hate you because they don’t understand you, but I do.” Unfortunately, she’s not very convincing in her pleas; Fridh’s delivery is intended to be serious but only registers as condescension, an echo of Vergérus.

Speaking of the man of reason, in a parallel conversation with Albert’s shrouded wife Manda (Ingrid Thulin playing Mr. Arman, a partial anagram to her character’s true identity), Vergérus reveals the relationship between incantation/illusion and God — the suspension of disbelief, rhetoric over evidence. “There are no miracles. It’s always the props and the patter that must do the work…. God is silent while men babble on.” Although he denies it, his speech brims with disdain for the Voglers as they represent “the inexplicable.” As Vergérus supposedly embodies Bergman’s critics, who attempt to dispel the thrilling metaphorical magic and meaning from art, the film sympathetically argues for some men’s need to maintain their illusions. Isn’t it interesting how the conflicted director powerfully overturns this idea in the next decade with his existential “God’s Silence” trilogy (Bergmans #4-6)? In the end, Bergman finds himself at a crossroads, indicative of The Magician‘s ambiguity, “an ending that mocks his own despair as a man and his failure as an artist.” So, remember: this humanizing, vulnerable reality may be of comfort to all the aspiring writers and filmmakers out there; even one of the greatest minds of his generation persistently faced intense periods of self-doubt which are reflected, perhaps inadvertently, in the literal title.

Official Bergman count: 21/45

- The Magician plays FREE on Sun, March 6, at the Chazen Museum of Art (750 University Ave) at 2:00p as part of ‘Ingmar Bergman in the Black and White.’ For more information on the series, shown exclusively on 35mm, please visit UW-Cinematheque’s official site.