An Oldboy poster I won at a college midnight screening years ago still hangs in my living room today. It’s a sad little testament to Chan-Wook Park as master storyteller and a supremely talented director, but a wrinkled poster isn’t necessary for such an argument when Stoker can say so much more. Park’s latest film is so stylish and so bizarre in ways that draw attention to themselves, but only in the best ways possible — that’s saying something a poster never could.

After her father dies in a car accident on her birthday, India Stoker (Mia Wasikowska) and her now-widowed mother (Nicole Kidman) are forced to pick up the pieces of their extremely chilly relationship. Things seem a little brighter though when India’s elusive Uncle Charlie (Matthew Goode) shows up, offering to help the Stokers in their time of grief. Charlie’s a great cook, a skilled gardener, a wine connoisseur, and a cultural sophisticate. There’s just something off about him. Maybe it’s his dead, cow-eyed stare or the fact that Charlie emerged so suddenly from obscurity after his brother’s death. Or maybe it’s the whole “belt strangulation” thing. Definitely one of those.

Immediately present in Stoker is not what it is, but rather how it is. Making flashcards with “lighting” and “staging” and “shot blocking” is one way to learn about film techniques, but Park Chan-Wook’s School for the Criminally Insane is so much better. Watch as he toys with sensory input, inserting audio overlaps that don’t line up, endless matches on action, and the greatest shot of a wheat field I’ll probably ever see. So much of Stoker is blended beautifully by a gorgeous reverence of the irreverent. In one bravura sequence, Park cuts across three separate events that still feel joined not just in time but in theme. A character discovers the basement freezer’s “secret” while another makes a bold sexual confrontation ans yet another incites a bolder, violent one. Park’s mastery of technique pulls the story together in ways that only expand on and never veer from Wentworth Miller’s (Prison Break) script. A hallucinated piano duet sees the camera push in and then pull out in a frenzy of orgasm and insanity. Where a lesser director might go too far with flourishes and showy techniques, Park’s “crazy” is fittingly measured.

That crazy makes for a fitting blend alongside Stoker’s oxymoronic properties. Park juxtaposes washed-out palettes with bright interiors, where green grass and garish playground slides seem so dull and empty next to a widow’s immense estate that’s as paralyzingly ornate as a trussed-up mausoleum. Park plays with his oxymorons as an exterior entry points not just into his characters’ variable insanity but as ways of illustrating Stoker’s obsession with “nature vs. nurture.” Does India change because her father raised her to do so? Is she acting out towards her mother? Or is this the inevitable result of uncontrollable impulses?

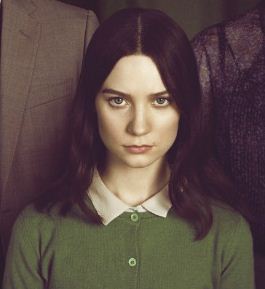

The uncertainty is as much a testament to Stoker’s leads as it is to Park’s technique. Nicole Kidman, never one to shy from a risky role, does “emotionally damaged” very well. She’s the detritus of a household torn asunder, and while her frailty is essential, the relationship between India and Charlie is the heart of Stoker — if it’s capable of having one, that is. His stiff confidence as Watchmen’s Ozymandias might have been a fluke, because Matthew Goode is excellent in a role where “just be Anthony Perkins” would be such a tempting approach. Goode is blessed with both a chiseled mannequin perfection and an inability to blink for long periods of time, and he puts both talents to use in his half-tormenting, half-courting of his niece. Mia Wasikowska also shows demonstrable range beyond the dull lead in Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland. India and Charlie’s relationship feels both of blood and of desire, and a doubling between their less than savory similarities is a point Park raises but never fully defines. We eventually become so ingrained in their insanity, why should Stoker provide a moral or contextual high ground in its resolution?

Ridley Scott once described Hannibal as his attempt to show romanticism in the grim and dastardly. Stoker succeeds at what Scott only attempted twelve years ago. In the wake of extreme loss, the really weird stuff comes out, and Stoker is immensely fluid and expressive in showing that. Park’s dizzying, elliptical direction crests both in wild showcases and the inconspicuous moments. In a film this crazy, no moment is more poignant than its calmest glimpse of India, in the middle of an art class on still lifes. While her classmates only see a vase and paint it accordingly, India’s canvas is covered in stunning a patchwork pattern. It looks nothing like the patterns on the vase, because India is painting from the inside, looking out.